Aerospace

Space-Based AI: The Next Frontier for Cloud Scale

Securities.io maintains rigorous editorial standards and may receive compensation from reviewed links. We are not a registered investment adviser and this is not investment advice. Please view our affiliate disclosure.

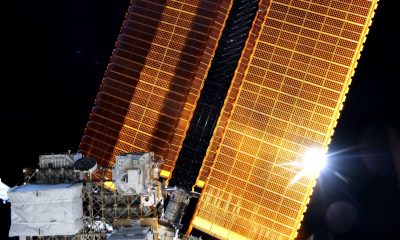

Why AI Infrastructure Is Moving to Orbit

As AI booms, several supply constraints have emerged. The first was GPUs, with specialized hardware moving from a niche gaming use to mass adoption by AI data centers. As a result, Nvidia (NVDA -0.05%), the leader of the sector, has grown into the world’s largest company.

But another limitation is becoming the main issue: energy supply.

This is because AI data centers are now measured not so much by their computational power, but by their power consumption. This is why AI companies are scrambling to restart nuclear power stations, secure the first SMR prototypes, or state regulators are putting new gas-fed power plants on a fast track for approval.

As the rush to find energy for data centers intensifies, eyes are turning to another option: space-based AI, giving a whole new physical meaning to “cloud computing.”

The possibility of an unlimited energy supply from orbital satellites is something we already analyzed extensively in “Space-Based Energy Solutions For Endless Clean Energy.”

But this concept is always somewhat limited by the need to convert solar energy into power, turn this electricity into microwaves to beam it back down to Earth, and then convert it back into power.

This increases the complexity of the power satellites, requires more ground-based infrastructure, and overall reduces the efficiency of the procedure drastically, as each conversion into a different form of energy leads to losses. This could likely only work with very cheap orbital launches.

Alternatively, if the power were directly used in orbit, this would be a lot more efficient and become economically viable sooner—especially if the final “product” can be easily sent back to Earth.

In theory, data centers in space could be the ideal option: they need a lot of power, but sending the results of the calculations back to Earth is trivial, requires no new infrastructure, and does not cause energy losses.

The idea is not just theoretical; for example, Alphabet/Google just announced “Project Suncatcher,” an orbital AI computation system prototype that we covered in “Google’s Project Suncatcher and the Rise of Orbital AI.”

So, could it work, and why could it be the next step in building AI infrastructure?

The Collision of Two Trends

Solving the Terrestrial Power Constraint

More energy than ever is needed to power human civilization, and the commercialization of LLMs has only increased the need for new power installations. So far, most newly installed power generation is solar energy.

Source: ARK Invest

But this poses a problem for terrestrial grids, as solar energy only produces power when the sun shines, resulting in lower production during cloudy days, winter, or in the evening. In contrast, power-demanding sources like AI data centers require a continuous supply of energy, with peak consumption often occurring in the evening and in winter.

In theory, this can be solved with cheap energy storage, like utility-scale battery parks. But in practice, this cancels many of the advantages of solar as a green and cheaper source of energy.

Source: ARK Invest

ARK Invest estimates that capital expenditure in power generation must scale ~2x to ~$10 trillion by 2030 to meet global electricity demand. Of this, deployments of stationary energy storage will have to scale 19x.

Source: ARK Invest

This will also require massive investment in the power grid, adding further to costs. Any alternative that skips battery and grid costs could be competitive, even with its own unique infrastructure costs, such as the orbital launch of space-based AI data centers.

The Starship Deflationary Cycle

It is no secret that SpaceX is the most successful space-focused company ever created. By unlocking reliable reusable launchers, the company has dramatically reduced the cost of lifting useful payloads to Earth’s orbit. Costs have declined by ~95%, from ~$15,600/kg to under ~$1,000/kg in the 17 years since 2008.

The new super-heavy launcher, Starship, will likely continue this trend and ultimately bring launch costs into the ~$100/kg range.

Source: ARK Invest

What has not yet been fully understood is that this does not just make satellites or space missions cheaper; it radically changes what can be done in space.

When putting a kilo of material in space costs only $100, sending anything useful or light enough into orbit becomes economically viable. This is true for thin-film solar cells, which can be very light when they do not need to be protected by glass or rigid metal frames against terrestrial weather.

This is also true for materials that are highly profitable on a per-kilo basis, such as computer chips.

For example, a full GB300 NVL72 Rack/Cabinet from NVIDIA costs as much as $4M but weighs only around 1.8 metric tons (4,000 lbs). The cost of sending such material into orbit at $100/kg is only $180,000—almost a rounding error relative to the hardware cost.

Of course, the total price would be higher when taking into account supporting equipment (shielding, cooling, power generation, etc.), but it means that getting an AI computing system into orbit will not massively inflate its costs soon. It is likely that the turning point is around $500/kg of launch costs.

Source: ARK Invest

As an extra bonus, the rise of orbital AI could further improve the economics of reusable rockets by creating a massive market to service. While finishing the Starlink constellation might require 11x the cumulative upmass lifted by SpaceX until 2025, 100 GW of AI compute would increase demand for orbital lift by another 60x. In turn, this volume will decrease launch costs further.

Source: ARK Invest

Why Orbital AI Has Structural Advantages

Swipe to scroll →

| Driver | Terrestrial AI Data Centers | Orbital AI Data Centers | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power availability | Constrained by grid capacity, fuel supply, and permitting timelines | Near-continuous solar potential in the right orbit; no grid interconnect | Orbital compute sidesteps the slowest part of AI scaling: power + permits |

| Capacity factor | Solar is intermittent; firming requires storage or dispatchable generation | High solar availability with reduced intermittency vs ground solar | Reduces or eliminates storage capex for power firming |

| Cooling overhead | High HVAC/heat-rejection loads; water constraints in many regions | Radiative cooling via large heat radiators; no water requirement | More compute per watt when cooling energy is lower (but radiator mass matters) |

| Latency & bandwidth | Excellent for interactive workloads; fiber backbones are dense | Best suited for batch/HPC, training, or asynchronous inference; relies on satcom links | Orbital AI likely starts with non-latency-sensitive workloads |

| Deployment speed | Land, permits, grid upgrades, and construction take years | Launch cadence becomes the gating factor if standardized platforms exist | A “manufacture + launch” model can compress time-to-capacity |

| Hard risks | Permitting, grid congestion, local water/thermal limits | Radiation, debris/collision, servicing, and end-of-life disposal | Orbital economics hinge on mitigating space-specific failure modes |

| Economic hinge | Power + interconnect + cooling capex dominate scaling | Launch + platform mass + on-orbit uptime dominate scaling | The crossover arrives when $/kg and standardized platforms drive down all-in delivered compute |

Perfect For Solar

Solar energy is abundant in space—up to 4x the output for the same nominal capacity, thanks to direct sunlight without atmospheric loss. In the right orbit, it is also much more reliable, shining 24/7 consistently.

This removes the limitations suffered by land-based solar power. In theory, this could be the final form of solar energy generation. However, due to the difficulty of bringing that power back to Earth, it will require ultra-cheap launch costs or in-orbit manufacturing to be economically viable.

Alternatively, simpler orbital mirrors shining on land-based solar farms, as championed by Reflect Orbital, might skip the light-to-microwave conversion losses.

In contrast, if power is used in orbit, none of these steps are required. Once computation is finished, the resulting data can be sent back to Earth using standard telecommunication methods, with satellite bandwidth improving quickly.

Natural Cooling

Another unique advantage of space-based AI data centers is cooling. When not exposed to the Sun’s radiation, space is extremely cold, standing at -148°F (-100°C) for a spacecraft in the shadow of the Earth or its own arrays.

A significant portion of terrestrial data center energy consumption comes from cooling. Locating them in the Arctic or even the stratosphere has been proposed, so space offers a natural advantage. This will likely require massive passive cooling systems to radiate away heat, but this is technically feasible.

Ubiquitous Satellite Intelligence

SpaceX and its broadband satellite network have completely changed the orbital landscape, with Starlink satellites making up roughly half of all satellites in orbit.

Source: ARK Invest

This has caused an exponential decrease in satellite bandwidth costs, dropping nearly 100x between 2020-2024, with further gains expected from Starship flights.

Source: ARK Invest

Telecommunication in space is becoming so ubiquitous and cheap that orbital data centers can use preexisting networks to communicate with Earth without the need to build dedicated capacity. Furthermore, a dense satellite network could lead to additional maintenance services, such as refueling or “towing,” which would increase the lifespan of these assets.

Separating Space & Land Infrastructures

Because orbital AI data centers do not connect to the regular grid, they will not impact power prices on Earth. If anything, the extra demand for solar technology will help make solar energy cheaper globally.

Furthermore, these centers will not need to wait for terrestrial grid upgrades, which can take years. The process also avoids the use of land and precious water resources, improving the overall economics.

Investing In Orbital AI

Broadcom

Broadcom Inc. (AVGO +0.33%)

Besides GPU producers and AI model developers, companies producing connectivity and specialized IT equipment for data centers are major winners of the AI boom. One major company in this category is Broadcom, a tech giant with roots dating back to the dot-com era.

Following the merger of Broadcom and Avago in 2016, the company’s activities are split between infrastructure software and connectivity hardware (wireless, servers, AI networks, etc.).

Source: Broadcom

Another growing AI-related activity is the design and manufacturing of XPUs, which merge the CPU, GPU, and memory into a single electronic device. Broadcom utilizes its experience in producing ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits) to create chips designed specifically for AI computing.

Source: Broadcom

These types of dense, energy-efficient computing units are a perfect match for orbital AI, which requires an optimized balance between performance and weight. ASICs’ higher energy efficiency is also a plus, as lower power consumption reduces the mass of solar panels needed in orbit.

Investor Takeaways:

- Core thesis: AI’s binding constraint is shifting from compute to power availability and permitting timelines; orbital compute is a potential structural workaround.

- Economic trigger: Launch costs approaching ~$500/kg materially widen the feasible payload mix (solar, radiators, shielding) for profitable orbital compute deployments.

- Early winners: “Picks-and-shovels” enablers—ASIC/XPU designers, photonics/co-packaged optics, and thermal management—benefit before any “pure-play orbital cloud” exists publicly.

- Key risks: Radiation hardening, on-orbit servicing logistics, and debris/collision risk can erode economics even if launch prices fall.

- Time horizon: Treat orbital AI as a long-duration infra theme; focus on firms monetizing terrestrial AI scaling today while building optionality for space workloads.